This ought to be a fairly short post.

I got the idea of it long ago while re-re-reading the excellent "The Death of Economics" by Paul Ormerod. This book, if you haven't read it already (and you should) is, as per the Wikipedia description linked above, constituted of two distinct parts. The first part is a long list of the short comings of various aspects of orthodox economics. It will come as a surprise to no one that I am more or less in total agreement with everything Ormerod says in that part.

In the second part, and very courageously, Ormerod tries to describe what a macro-economic model should look like. Again, the wiki article summarizes the thesis well:

"Three properties are identified as essential to any model seeking to explain unemployment. First the model should be capable of settling into long periods of regular fluctuations; second, such fluctuations should be sensitive to the initial values of the system; thirdly, following a major shock, there should be no tendency to settle back to the regular behaviour previously seen".

Again, I have no dispute with such properties describing not only unemployment but a variety of economic phenomenons. So, should you just stop reading my stupid blog, buy the book and be done?

Well, not quite.

In attempting to explain the economic cycle and macro-economics, Paul Ormerod, having eviscerated orthodox neo-classical economics, returns to the classics and reminds us that a lot of them, being concerned with practical matters, rather than just mathematically complex equations, gave a central role to profit margins in explaining the economic cycle.

Stated shortly, the idea is that, when profit margins are high, companies and entrepreneurs rush to invest, expand and develop but that such activities eventually, through competition, lead to a lower rate of returns, at which point capitalists reduce their investments and so the economic activity cools down until profit margins are restored to an attractive level.

And Paul Ormerod thought he had found a correlation between profit margins and economic cycles.

But, if profit margins are the driver he (and some of the classics) thought they are, why are we in a recession/crisis right now? Profit margins have never been stronger!

So, clearly, whatever relationship Ormerod thought he had (re)discovered must actually be fallacious.

Or is it? The logic chain seemed pretty impeccable - lots of profit opportunities = lots of investments = lots of growth until competition exhausts opportunities = recession until profit margins recover...

And I think there is something to this reasoning. Except that entrepreneurs and corporate leaders are somewhat less sophisticated in their investment decision-making that the classics presupposed - let alone modern-day investment bankers or consultants with their cash flow projections, models, NPV and IRR.

All these tools mostly hide the fact that investment decisions are, in my humble opinion and experience, driven by top line revenue growth.

If the economic environment is deemed conducive, investments are made. It is assumed that the business knows enough about its sector to control its costs and be profitable i.e. profit and profit margins are a result, a derivative. This is even truer if the investment is to represent a departure from the company core competencies. Venture - risky/unusual - investments tend to be made only when a buoyant economy lift the mood of executives and convince them that it's okay to move outside of their comfort zone.

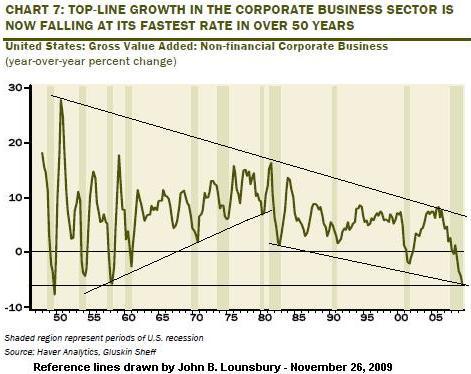

Despite all the big talks about the profitability of the business, the profit margin is not targeted in and of itself. It is not the driver of the investment decision. The top line is. You only have to look at the chart below to see why, despite extremely low interest rates and fat profit margins, businesses are not rushing to invest...

Saying the same thing a bit differently, in a crisis or recession, businesses obviously do their very best to slash costs to respond to the decrease in the top line and thus you can have the paradox of a crisis leading to better profit margins.

Those profit margins, however, do not reflect many new investment opportunities. Asides from tighter general cost controls, they reflect labour constriction.

But, just as in the Paradox of Thrift where the rational desire to save at the individual level led to the irrational result of the whole being unable to, the attempt by every company to slash its labour costs lead to a diminishing top line growth for the whole since the revenue of any company is someone else's spending, ultimately by individuals.

Now, it is easy enough to call all of the above tautological. It is clear that the chain of event is crisis comes first, top line get slashed, labour costs get squashed, profit margins may go up (if the squashing of costs occurs faster than the slashing of the top line) and we still haven't explained why there was a crisis in the first place.

Well, I think crises can occur for several reasons. For someone who tend to reject Equilibrium-thinking in economics, the truth is that, in my opinion, there is an optimum range for profit margins and labour's share of income. Both too-high/too-low a number reflects a disequilibrium and a problem. Just as with trade balance being best when hovering around zero, you want neither too much nor too little of profit or salaries.

Profit margins need to be high enough to attract and compensate capital "reasonably" (both equity and debt) as well as to allow for R&D, depreciation etc. At the same time, labour's income share needs to be high enough to sustain top line growth/top line stability. Whether the self-sustaining range is 62 to 66% or 65 to 70%, I do not know but it is out there and ignoring it is bad news.

For without this balance, the economy can go and does get into a vicious cycle that can be papered over for a long while with debt but will ultimately result in the situation we have today.

And corporations doubling down on the slashing of labour in conjunction with the unraveling of social safety nets can only make things worse.

Said differently, despite some few recent positive numbers, we're not out of the woods yet. We need to see Labour's share rising again before we can be said to be safe.

And corporations doubling down on the slashing of labour in conjunction with the unraveling of social safety nets can only make things worse.

Said differently, despite some few recent positive numbers, we're not out of the woods yet. We need to see Labour's share rising again before we can be said to be safe.

Psrt of this is reasoning in the middle of a transient. Another part is that in the US, at least, (data from some years back) that while cash flow remained reasonably constant as a percent of sales after things stabilized after WWII, reported earnings declined.

ReplyDeleteThe reason is that inch by inch (and every day) some industry gets a new writeoff added to the tax code so that the share of taxes from corporations has dropped from 8% of GDP to 2%, and the official "profit margin" has become less and less comparable over time. So you need a better measure than any published "profit margin".

The current lack of balance in the US is that there is a huge pile of unallocated debt. Basically the banks have strong reasons to avoid admitting it, because it would impair their capital. They can eat it slowly over years, while maintaining the fiction that they are solvent. However, this paralyses all concerned since the borrowers are not free to move on, nor are the banks.

The TARP fund would have been better used to do what is was designed for (supposedly) and buy up the dud mortgages into a "bad bank" and proceed to clean up the mess so that millions of home owners could get on with life. Instead the lawyers win.

Right now there is a lot of fog between us as the future, and it is hard to come up with the sort of convincing case for the new investment until some of that fog clears.

I think you are on the right track starting with

"top line growth" but what is the definition of it?

Hi, retired

DeleteAnd welcome to the party! It's great (and gratifying) to see new posters.

As to your points, I think that the profit margins and the IRS declared profits are not necessarily in line. Tax treatments, as you say. But profit margins at 15% seem to reflect that big businesses (at least) are printing money. And indeed, if you take their cash positions, they have big pile of money sitting idle.

I think that there might have been a point in 2008/2009 where banks would have been declared insolvent if they had had to mark-to-market their potential losses. But I think that, no fear, the banks are now, thanks to unlimited federal money and Fed support, in the clear, no matter how bad their books really were.

Again, as I said in response to a recent Noah Smith about interest on reserves, I really don't think that lack of lending right now is anything more than the banks having difficulty finding credit-worthy clients and people/businesses being quite careful about adding more debt now.

I mean, I've been trying to raise capital for clients - i.e. I've been in contact with people trying to take on debt - and the banks were NOT eager. Sure, they all say they're open for business but if you're not already well established and flushed with cash, they're fearful. OTOH, if you're well established and flushed with cash, why would you take a loan? Interest rates are low but that's not quite enough.

I fail to understand your question about 'top line growth'. I would be referring to S&P 500 companies' revenue. I suspect you're trying to say something and I am failing to catch your drift. Can you precise your thought?